Options Trading

There are two kinds of options: calls and puts.

A call is the right to buy something at a certain strike price regardless of the market price.

A put is the right to sell something at a certain strike price regardless of the market price.

Calls and puts have 3 key components:

The thing (stock, commodity, etc.) to which the option pertains

Strike price: the price at which the thing can be bought or sold

Expiration date: the date on which the option expires

The price at which options trade is called the premium.

The buyer of an option is buying the right to buy (call) or sell (put) the stock in question

at a the strike price on or before the expiration date.

Options are traded in batches of 100; each batch of 100 is called a "contract".

Options can be compared to insurance. Those selling options are the insurance company, buyers are the insured.

The buyer is paying an up front premium to protect himself against future volatility in the stock

by ensuring he can trade it at a prearranged price regardless of its future market price.

Perhaps the most intuitive example is farming. Farmers may buy "puts" on the crops they are growing.

This guarantees they can sell their crop at a prearranged price even if the market tanks.

If the market goes up, the farmer can sell at the higher market price.

In this case the farmer doesn't exercise his "put" option.

It expires unexercised and the seller of the option keeps the premium.

This is like carrying insurance and never filing a claim.

But if the market tanks, the farmer exercises his "put".

This forces the seller of the option to pay the strike price for the farmer's crop.

In short, the farmer pays an up-front premium to insure himself against the volatility of the crop market.

What determines the price at which options sell?

One factor is the strike price.

The difference between the strike price and the current market price represents an "intrinsic" value to the option.

This value can be negative or positive.

For example, a "put" whose strike price is below the current market price has negative intrinsic value.

However, due to other factors, an option with negative intrinsic value may have a positive premium.

Another factor is time value.

The further into the future the expiration date is, the more uncertainty there is.

Thus, options with longer contracts - whose expiration is further into the future - tend to have higher premiums.

One factor is the degree of future uncertainty or volatility.

If the future seems stable then premiums will be low -

there is less perceived risk so people won't feel the need to insure themselves.

Another factor is interest rates.

If interest rates are high, options sellers get bigger effective premiums because money paid up front is worth relatively more.

From the option buyer's perspective, high interest rates means the money paid up front is more expensive.

Both of these perspectives mean high interest rates tend to push down option premiums.

Options that have positive intrinsic value are called "in the money".

For example, a "put" whose strike is above the current market price,

or a "call" whose strike is below the current market price.

But just because an option is in the money doesn't mean it will be exercised.

For example, suppose farmer Joe buys a "put" on his corn with a $400 strike and pays a $40 premium.

A few weeks later corn is trading at $380.

Farmer Joe's options are in the money.

But he won't necessarily exercise them because even though he'd make $20 better than market,

he paid $40 for the option so he still comes out behind.

If farmer Joe's options are still in the money on the day they expire, he will exercise them.

That's because he knows he'll never get the premium back.

So even if he loses money overall, the profit he makes in the price differential helps

offset the cost of buying the option.

Options are often described as "high risk" and not suitable for average investors.

This is incorrect and misleading.

Options can be high risk if used poorly.

But used properly, options can actually REDUCE trading risks compared to simple buying & selling of stocks.

There are myriad different investment strategies involving options.

Here I will describe a very simple strategy for investors who are long on particular stocks.

This strategy offers greater potential gains with lower risks than buying stocks outright.

TRADING EXAMPLE

Suppose you've done all your research and decide to buy a piece of Foo as a long term investment,

part of your already diversified portfolio.

Let's say you're going to invest $100k and Foo is trading at $25.

You could simply buy it outright - buy 4000 shares of Foo.

Doing this, you immediately put $100k at risk.

The potential benefit is any long term upside growth.

Using options you can increase the gain and reduce this risk.

Instead of buying 4000 shares of Foo, sell 40 "put" contracts on Foo with a strike of $25.

You can pick any time frame you want, so for simplicity let's pick a date one month in the future.

Suppose the premium for this put is $1.

When you sell the put you immediately get $4000 in cash,

which you invest as you like, but keeping it reasonably liquid so it's available if you need it

(you'll read why below).

Basically you're agreeing to support (buy) Foo at $25 for the next month.

This is called "selling to open".

You're selling the put, and you will be holding the contract so you are "opening" interest in the option.

This is also called a "naked" put - you are agreeing to buy the stock at a future date.

If you had already sold this stock short, it would be a "covered" put.

That's because by selling short you already assumed the liability of buying it in the future,

so underwriting the put doesn't increase your liability.

The upside:

If a month goes by and Foo is still at or above $25, your puts expire and you keep the $4000.

In a nutshell, you put only $96k at risk instead of $100k,

and you earned a 50% APR on it.

That is to say, you earned $4000 on a $96000 potential liability, in a single month,

and not only did you do it without paying anything up front,

you actually got paid up front the day of your trade.

But what is the risk?

Let's look at the worst case scenario: Foo tanks to zero and your puts are exercised.

In this case you buy Foo at $25, so you are out $96k: $100k minus the $4k premium you already recieved.

This may sound bad, but remember that if you bought Foo outright you'd be out $100k.

So the worst case using options is $4000 better.

There is another form of risk.

If the stock shoots upward you lose the upside beyond your premium.

You do keep the premium and make a profit,

but if the stock goes up by more than your premium then you would have made more money if you had bought it outright.

In summary, selling a naked put is less risky than buying a stock outright,

because you keep the premium even if the stock tanks.

But you also give up potential gains beyond the premium.

So which is better - selling the put or buying the stock?

It depends on the details of the option and the stock, and probability.

PROBABILISTIC BUY

The above buying strategy is what I call a "probabilistic buy".

You are committing to buy the stock under certain conditions that may or may not occur.

It reduces the risk of buying the stock outright and generates cash up front.

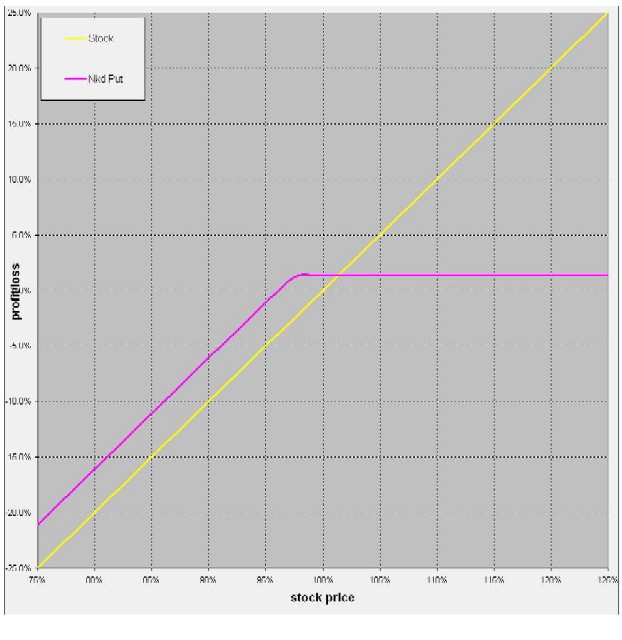

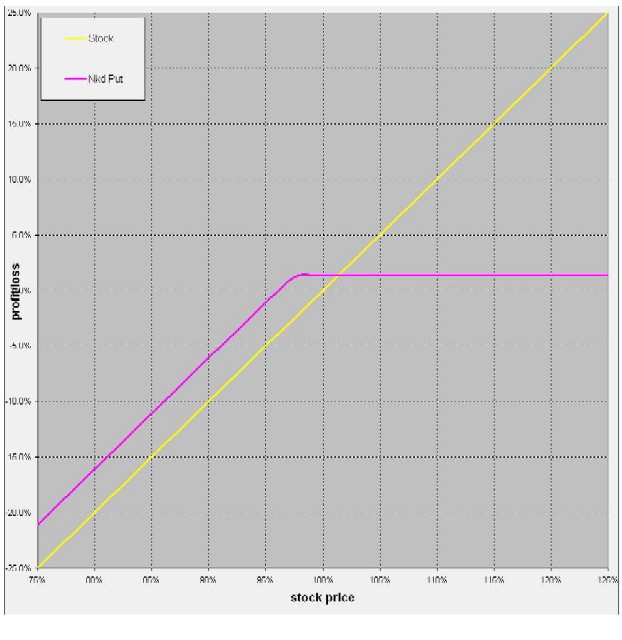

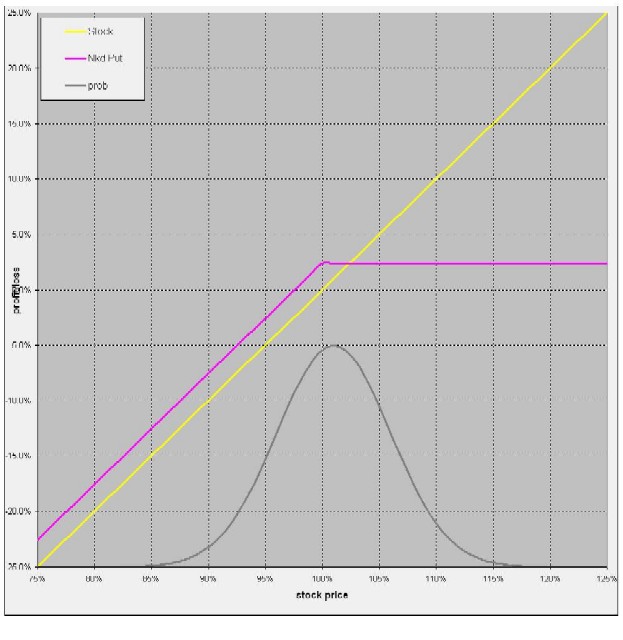

Selling a naked put is often compared to buying a stock by drawing a profit/loss curve.

Stock price on the X axis (current price in the center), with profit/loss on the Y axis.

Looking at this curve, it appears that the naked put (pink) is not a good deal compared to buying the stock (yellow).

The downside is better - if the stock goes flat or downward in value you lose less money.

But the upside is much worse - your profit is fixed at the premium so if the stock goes through the roof you lose all that upside.

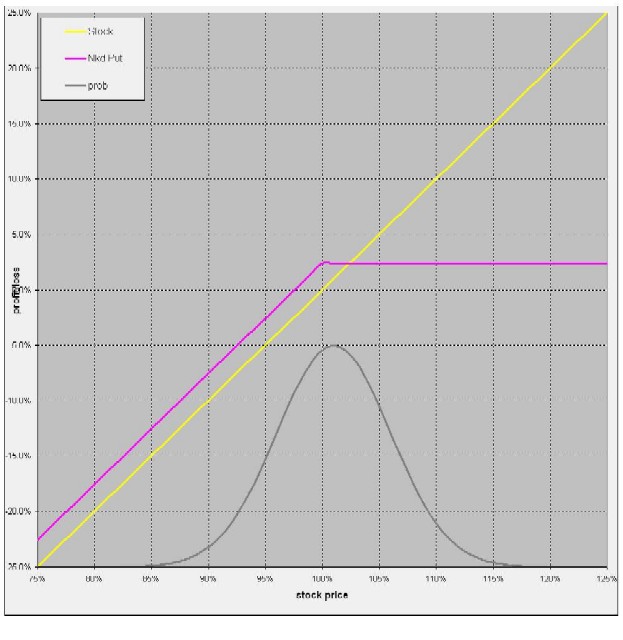

But this analysis is misleading because not all of these future outcomes are equally probable.

We know, for example, that a month from now, the stock's value is more likely to be within 10% of its current value,

than it is to tank to zero or to double.

So on the profit/loss curve, the points near the current value of the stock are more likely to occur

than the points at the far left and right edges.

One way to picture this is to apply a standard normalization distribution to the future outcomes depicted on the profit/loss curve.

The height of the grey curve shows the relative probability of future stock prices.

The center region of the curve (around the stock's expected future value based its historical growth)

is where the most probable outcomes are.

The price range of the distribution and how much more probable this area is - depends on the stock's volatility.

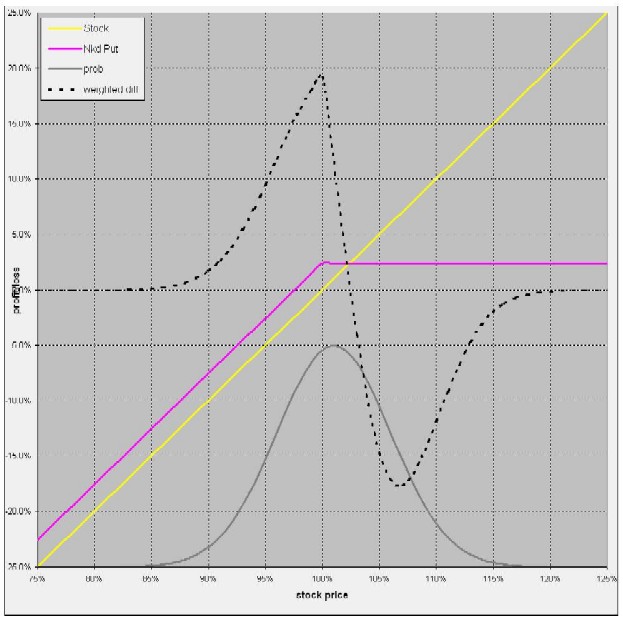

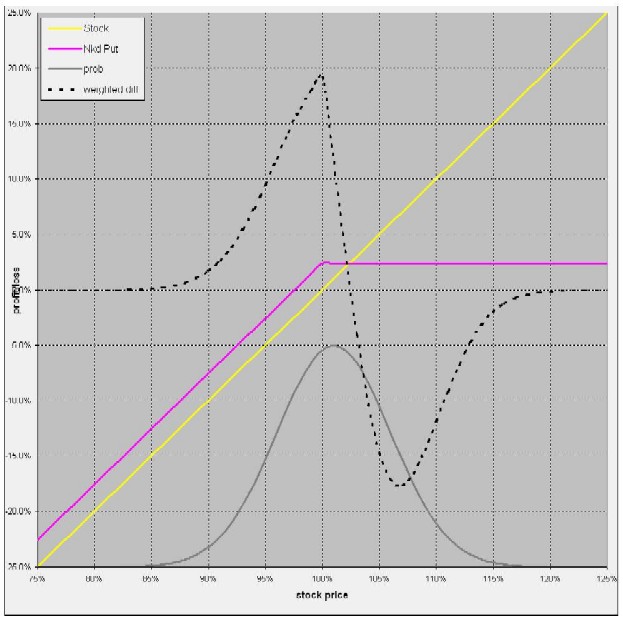

To complete the picture, we plot a third curve.

Each point is the difference in profit multiplied by the probability for that outcome.

This gives an intuitive yet realistic picture of how a naked put compares to buying a stock.

The shape of this curve will vary depending on the premium, time duration and strike price of the put.

Now it is easy to see how misleading that first graph was.

Treating all future outcomes as equally probable totally distorts the risk/benefit analysis.

All future outcomes are not equally probable!

This is not to say that a naked put is always a better deal than buying a stock.

But to choose between them, one must know how to compare them properly.

EXIT STRATEGY

At any time, you can buy back any options you sell.

Suppose a week later you decide you don't want these "put" contracts hanging over your head.

Or suppose you see Foo starting to tank and you want to get out before the worst happens.

You simply buy back your "put" options.

That is, use the cash you were already paid when you sold the puts, to buy them back again.

The price may have changed between then and now; it may have gone up or down.

If the price went down, you pay less than you sold them for.

The difference is your profit and you are out of the contract (sold it to somebody else).

If the price went up, you will take a loss.

You have to compare that against holding the option to its exercise date and decide whether it's worth it.

This is called "buying to close".

You are buying the put, and no longer held to the contract - "closing" your interest in the option.

Just like with simple stock trading, it's usually a bad idea to jump in and out of - or day trade - the options market.

The temptation to do this is often a sign that you aren't confident with your research and decisions.

But the point is, options never "lock you in" until contract expiration.

You can buy & sell in and out any time you like.

OPTION EXERCISE

Suppose Foo drops below $25 and your options are exercised.

This means you buy Foo at $25.

You are still better off than if you had bought Foo outright.

The premium you were already paid reduces your effective price.

Because you got a $1 premium, you're effectively buying it at $24, not $25

(actually less than $24 because of interest - you got the $1 premium up front, long before buying the stock).

Second, you are paying the same price later in time.

Meanwhile, you've been earning interest on the premium you were paid up front.

So now you own Foo.

But this isn't bad - indeed, it was your original intent to invest in Foo.

This takes us to the next step of the investment strategy.

Now at this point the observant reader says,

"But if the puts are exercised that means Foo dropped below $25,

so I'm always paying more than market price for them."

This is true - however, if you had not used options, instead had bought Foo outright,

then you paid $25 for it anyway.

Using options, you only paid $24 for it (actually a bit less than $24).

PROBABILISTIC SELL

Now that you own it, you want to benefit from its expected long term growth.

Suppose your investment goal for Foo is to earn 20% - to sell at $30.

Instead of passively waiting for it to hit $30, sell call options with a strike of $30.

Because you already own Foo, this is a "covered" call.

Writing a call contract obligates you to sell Foo at a certain strike price.

But since you already own Foo, this is not any new liability -

if exercised, you simply sell the Foo you already own

(you don't have to go out and buy it).

For our example, we'll go one month out again

(there's nothing magic about one month expirations, it's just a time frame to keep things simple).

Suppose Foo calls one month out at a $30 strike have a $1 premium.

You sell 40 contracts of Foo and pocket (another) $4000.

If they expire unexercised, you keep the premium -

and do it again the next month.

If exercised, you sell at $30 which means you achieved your investment goal.

But not only did you achieve your goal of $30 (a 20% gain),

you also got $4000 going in, and another $4000 coming out.

That's an extra $8000 which is another 8% on your investment.

If it took more than one cycle to get in or out

(you had options expire unexercised) then you earned even more.

This is called "selling to open" the call.

You're selling the call, assuming the contract - "opening" your interest in it.

It's a "covered" call because it doesn't increase your liability.

You already own the stock, so you won't have to go buy it if the options are exercised.

So what's the risk?

It's zero risk to you because you already own the stock.

When selling covered calls the only thing you forgo is upside potential beyond your investment goal.

Don't get greedy - just set your strike prices and gauge against premiums according to your goals.

CAVEATS

If this is so great why don't financial gurus advise people to do it?

I can think of only two reasons:

Ignorance: either they don't know about it, or they assume the average person can't understand it.

Fear: they are afraid of this strategy, or afraid the average person will get greedy,

get in over his head and lose his money.

This is rather ironic, because both of the above points apply equally well to simply buying & selling stocks outright.

Using options in the manner described above is not a "get rich quick" scheme,

but just a simple way to reduce risk & increase gains.

Here are some important points to keep in mind when using this strategy:

Don't get greedy.

Make sure your total liability if all puts are exercised is well within your means,

and no more stock than you would be willing to buy outright.

Of course this applies to all investment strategies.

Invest, do not spend, the premiums.

Don't go buy a boat or an airplane with your option premiums.

If you decide to buy out and close your position, you won't have the cash to do it.

Or if your puts get exercised you already spent the money you need to buy the stock - whups.

Choose stocks carefully.

Only sell puts on stocks you have researched and want to own or invest in.

Don't sell puts on a stock just because they have high premiums.

If the premium is high, there's usually a reason for it.

It's a sign of high volatility and risk.