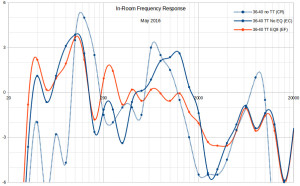

First let’s cut to the chase: in-room far-field frequency response measured at the listening position using 1/3 octave warble tones, measured with a Rode NT1-A mic, corrected for mic response

- The red line is what you hear – near perfection!

- The solid blue line is with room treatments, but without EQ

- The dotted blue line is without room treatment

In short, you can see that room treatment (huge tube traps and copious use of thick RPG acoustic foam) made a huge difference. Then EQ finessed that to something near perfection.

Aside: this FR curve makes me wonder why people often say Magnepans don’t have good bass. Mine are near-flat to 32 Hz (and you can hear 25 Hz) with a level of taughtness, speed and clarity that few conventional speakers can match. A subwoofer can go lower, which is great for movies and explosions, but most lack the accuracy and refinement needed for serious music listening.

Now, for the details:

I’ve been an audiophile since my late teen years, long before my income could support the habit. As an engineer and amateur musician I always approached this hobby from a unique perspective. The musician knows what the absolute reference really sounds like – live musicians playing acoustic instruments in the room. The engineer believes objectivity – measurements, blind listening tests, etc. – is the best way to get as close as possible to that sound.

Part of this perspective is being a purist, and one aspect of being a purist is hating equalizers. In most cases, EQ falls into one of 2 categories:

- There are flaws in the sound caused by the speakers or room interactions, and instead of fixing them you use EQ as a band-aid. This flattens the response but leaves you with distortions in the phase or time domain, like ringing.

- You don’t want to hear what live acoustic music really sounds like, you prefer a euphonically distorted sound and use an EQ to get it.

Equalizers are the dark side of audio. Powerful and seductive, yet in the end they take you away from your goal: experiencing music as close as possible to the real thing. Recently I traveled to the dark side and found it’s not such a bad place. Share my journey, if you dare.

I had my audio room here in Seattle dialed in nicely after building big tube traps, thick acoustic foam and careful room arrangement based on repeated measurements. However, it still had two minor issues:

- A slight edge to the midrange. From personal experience I describe it as the sound I hear rehearsing on stage with the musicians, rather than being in the 2nd row of the audience.

- The deepest bass was a bit thin, with 30 Hz about -6 dB. I have a harp recording where Heidi Krutzen plays the longest strings, which have a fundamental around 25 Hz. I could hear this in my room, but it was a subtle whisper. It would be nice to hear that closer to a natural level.

My room treatments made a huge improvement in sound (and I have the measurements to prove it). But I don’t know of any room treatment that can fix either of these issues. The sound was very good both objectively (+/- 4 dB from 35 Hz to 20 kHz at listener position) and subjectively, and I enjoyed it for years. Then I got the LCD-2 headphones and Oppo HA-1 DAC. As I listened to my music collection over the next year (a couple thousand discs, takes a while), I discovered a subtle new dimension of natural realism in the music and wanted to experience that in the room.

Since my upstream system was entirely digital, equalization might not be as terrible as any right-thinking purist audiophile would fear. I could equalize entirely in the digital domain, no DA or AD conversion, before the signal reaches the DAC. And since the anomalies I wanted to correct were small, I could use parametric EQ with gradual slope, virtually eliminating any audible side effects.

That was the idea … now I had to come up with an action plan.

After a bit of Googling I found a candidate device: the Behringer DEQ2496. Price was the same on B&H, Adorama and Amazon, and all have a 30 day trial, so I bought one. The DEQ2496 does a lot of things and is complex to use and easy to accidentally “break”. For example, when I first ran the RTA function, it didn’t work. First, the pink noise it generates never played on my speakers. After I fixed that, the microphone I plugged in didn’t work. After I fixed that, the GEQ (graphic equalizer) settings it made were all maxed out (+ / – 15 dB). Finally I fixed that and it worked. All of these problems were caused by config settings in other menu areas. There are many config settings and they affect the various functions in ways that make sense once you understand it, but are not obvious.

NOTE: one easy way around this is before using any function for the first time, restore the system default settings, saved as the first preset. This won’t fix all of the config settings; you’ll still have to tweak them to get functions to work. But it will reduce the amount of settings you’ll have to chase down.

In RTA (room tune acoustic?) mode, the DEQ2496 is fully automatic. It generates a pink noise signal, listens to it on a microphone you set up in the room, analyzes the response and creates an EQ curve to make the measured response “flat”. You can then save this GEQ curve in memory. You have two options for flat: Truly flat measured in absolute terms, or the 1 dB / octave reduction from bass to treble that Toole & Olive recommend (-9 dB overall across the band). This feature is really cool but has 2 key limitations:

- It has no built-in way to compensate for mic response. You can do this manually by entering the mic’s response curve as your custom target response curve, but that is tedious.

- It provides only 15 V phantom power to your mic. Most studio condenser mics (including my Rode NT1-A) want 48 V, but aren’t that sensitive to how much voltage they get and work OK with only 15 V. But you always wonder how much of the mic’s frequency response and sensitivity you lose when you give it only 15 V. Perhaps not much, but who knows?

The GEQ settings the DEQ2496 auto-generated were too sharp for my taste, so I looked at the FR curve it measured from the pink noise signal. This roughly matched the FR curve I created by recording 1/3 octave warble tones from Stereophile Test Disc #2. Since both gave similar measurements, I prefer doing it manually because I can correct for the mic’s response, and my digital recorder (Zoom H4) gives the mic full 48 V phantom power.

So the curves match: that’s a nice sanity check – now we’re rolling.

Using the DEQ 2496, I created parametric EQ settings to offset the peaks and dips. This enabled me to use gentle corrections – both in magnitude and in slope. I then replayed the Stereophile warble tones and re-measured the room’s FR curve. The first pass was 2 filters that got me 90% of the way there:

- +4 dB @ 31 Hz, 1.5 octaves wide (slope 5.3 dB / octave)

- -3 dB @ 1000 Hz, 2 octaves wide (slope 3 dB / octave)

These changes affected other areas of the sound, so I ran a couple more iterations to fine tune things. During this process I resisted the urge to hit perfection. Doing so would require many more filters, each steeper than I would like. It’s a simple engineering tradeoff: allowing small imperfections in the response curve allows fewer filters with gentler slope. Ultimately I ended up with near-perfect frequency response measured in-room at the listening position:

- Absolute linearity: from 30 Hz to 20 kHz, within 4 dB of flat

- Relative linearity: curve never steeper than 4 dB / octave

- Psychoacoustic linearity: about -0.8 dB / octave downslope (+3.9 dB @ 100 Hz, -3 dB @ 20 kHz)

The in-room treble response was excellent to begin with, thanks to the Magnepan 3.6/R ribbon tweeters. Some of the first EQs impacted that slightly, reducing the response from 2k to 6k, so I put in a mild corrective boost.

Subjectively, the overall before-after differences are (most evident first):

- Midrange edge eliminated; mids are completely smooth and natural, yet all the detail is still there.

- Transition from midrange to treble is now seamless, where before there was a subtle change in voicing.

- Smoother, more natural bass: ultra-low bass around 30 Hz is part of the music rather than a hint

- Transition from bass to lower midrange is smoother and more natural.

In other words, audiophile heaven. This is the sound I’ve dreamed of having for decades, since I was a pimpled teenager with sharper ears but less money and experience than I have now. It’s been a long road taken one step at a time over decades to get here and it’s still not perfect. Yet this is another step toward the ideal and now about as close as human engineering can devise. The sound is now so smooth and natural, the stereo stops reminding me it’s there and enables me to get closer to the music, which now has greater emotional impact. And it’s more forgiving of imperfect recordings so I can get more out some old classics, like Jacqueline DuPre playing Beethoven Trios with Benjamin Britten and Arthur Rubinstein playing the Brahms F minor quintet with the Guarneri.

Throughout this process, I could detect no veil or distortion from the DEQ2496. The music comes through completely transparently. I measured test tones through the DEQ2496 in both pass-through and with EQ enabled; it introduced no harmonic or intermodulation distortion at all. That is, anything it might have introduced was below -100 dB and didn’t appear on my test. This is as expected, given that I’m using it entirely in the digital domain – no DA or AD conversions – and my EQ filters are parametric, small with shallow slope.

While I was at this, I created a small tweak for my LCD-2 headphones. Their otherwise near perfect response has a small dip from 2 to 8 kHz. A little +3 dB centered at 4.5 kHz, 2 octaves wide (3 dB / octave, Q=0.67) made them as close to perfect as possible.

Overall, I can recommend the DEQ2496. Most importantly, it enabled me to get as close to humanly possible to perfect sound. That in itself deserves a glowing recommendation. But it’s not a magic box. I put a lot of old fashioned work into getting my audio system in great shape and used the DEQ2496 only to span that last %. Like any powerful tool, the DEQ2496 can be used for evil or for good. So to be fair and complete I’ll list my reservations:

- The DEQ2496 is not a magic band-aid. You still need to acoustically treat and arrange your room first to fix the biggest problems. After you do that, you might be satisfied and not need the DEQ2496.

- The DEQ2496 is complex to use, creating the risk that you won’t get it to work right or you’ll get poor results.

- To use the RTA feature you’ll need an XLR mic with wide, flat frequency response.

- I cannot assess its long term durability, having it in my system for only a few days. Many of the reviews say it dies after a year or two, but they also say it runs hot. Mine does not run hot, so maybe Behringer changed something? Or perhaps mine runs cooler because I’m not using the D-A or A-D converters. It does have a 3 year manufacturer warranty, longer than most electronics.