Mountain flying in small single engine airplanes adds potential risks. But there are things pilots can do to minimize these risks and do it safely.

Night: don’t do it. Night adds risk, mountains add risk. Either alone can be safe if you take precautions. But don’t combine them.

Fuel: use a bigger fuel reserve because there is greater chance to be delayed – either having to take an alternate route, or due to strong wind. But don’t simply top off the tanks if you don’t need to because that can add unnecessary weight, impairing performance. Flying in mountains at high DA, you need all the performance you can get. Normally, I plan to land with at least 1 hour of fuel in the tanks. When flying in mountains I increase this to 90 minutes.

Water: you’ll be at high altitude which is dehydrating. Bring plenty of water for everyone on board.

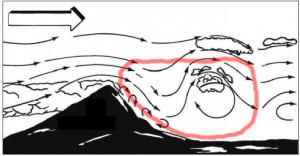

Wind: understand how wind flows around mountains and plan accordingly. Here’s a great picture I got by Googling:

- I’ve circled in red the areas you should never fly. Here be dragons: down-drafts and turbulence.

- Nasty wind effects begin at around 20 kts. If the UA forecast shows winds this strong over the mountains you’re crossing, consider an alternate route or be at least 50% higher than the highest ridge (see below).

- Crossing mountains against the wind is super nasty:

- First, you have the obvious: a headwind which slows down your ground speed and kills efficiency – and you’re at high altitude where winds are generally stronger.

- Second, the downwind side of the mountain has strong down-drafts, so you need to climb just to maintain level altitude, which saps speed and efficiency even further.

- Third, the downwind side also has a lot of turbulence. The last time you need turbulence is when your ground speed is slow and you are fighting down-drafts.

- Fourth, you are at high altitude, where your engine has less power and your prop & wing are less efficient. Just when you need power and efficiency the most, you don’t have them.

- Nasty wind effects exist from the surface to about 50% higher than the height of the ridge. For example if you’re crossing an 8,000′ mountain on a windy day, you need to be at least 12,000′ high to avoid the worst down-drafts and turbulence, though you will still feel some mountain wind wave effects.

- Climb early. Know how high you need to be and get there well before you reach the mountains. If you get too close before climbing, you may get stuck in down-drafts making it impossible to climb to the altitude you need.

To summarize, if you’re flying over mountains here are ways to minimize the risk:

- Do it during the day.

- Have more fuel than you need, but not so much you’re unnecessarily heavy.

- Climb to 50% higher than the highest ridge at least 50 miles before you reach it.

- This is not necessary with calm or very light winds.

- If you’re going against the wind, use full power properly leaned. At 10,000′ your engine only makes about 70% of its rated power. You need it all, and in the high altitude cool thin air you can’t hurt the engine.

- If you get into mountain waves, ride them instead of fight them.

- If they’re smooth and gentle, let them push you up or down at least 500′ before counteracting them.

- If they’re pushing you too far up, maintain power, nose down & gain some airspeed.

- If they’re pushing you too far down, maintain power, nose up to Vy if necessary to minimize the altitude loss.

- Remember at sea level Vx is always slower than Vy. As you climb Vx gets faster, Vy gets slower, until they meet, which is your airplane’s absolute ceiling.

- If you’re going against the wind, after you reach the top of the highest ridge you’ll be in an up-draft with a lot of altitude you no longer need. Nose down and convert all this energy into airspeed. You’ll regain some of the lost time and efficiency.