Summary

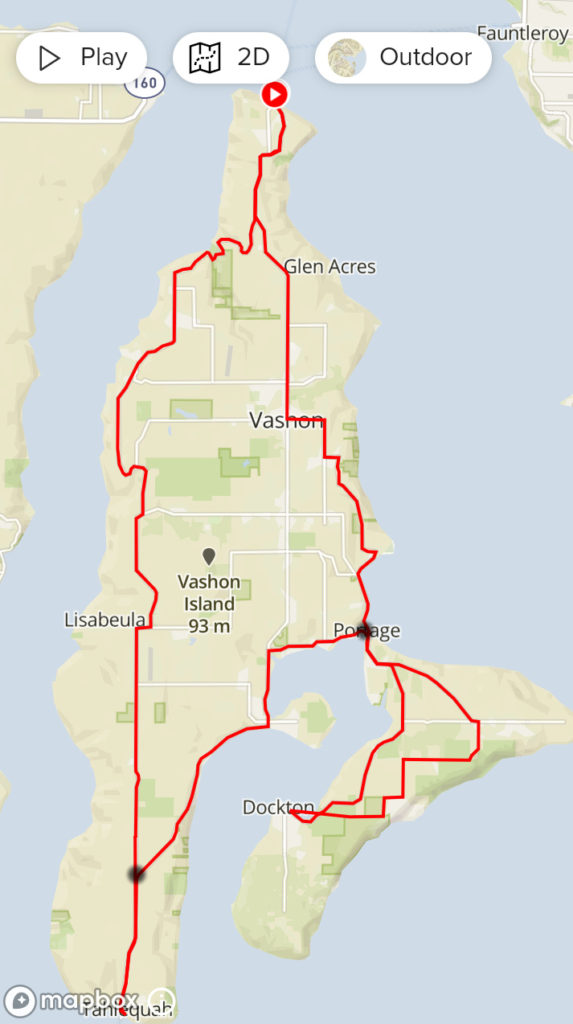

The White Rim Trail is SW of Moab Utah. It follows the Colorado River SW to its junction with the Green River, then NW up the Green River, making a rough “V” shape, then a mix of dirt & paved roads connect the top of the V. It makes a loop measuring 100 miles, about 8000′ of cumulative climb. The trail ranges from simple dirt/rock, to sand, to rugged steep technical with big rocks. Along the route there is no food, water or services. And mostly no cell/mobile coverage.

Most bicycle tours take 3-4 days to do this trail, supported with 4WD vehicles providing food, water and shelter. It is possible to ride it in a single day, but it’s a big physical effort that also takes some planning. It helps to have a gung-ho friend named Stefan to convince you to ride it with him.

Stefan rode WRIAD solo in Oct 2020, and he and I rode it together in Oct 2022. This describes what it was like and how we prepared for it.

Pics here: http://mclements.net/Moab-202210/

Here’s the GPX track overlaid with Google Earth, which underestimates the mileage and elevation because it over-smooths and simplifies the track. The red flag is our start/end point. The spike in speed around mile 75 is a GPS glitch.

Preparation

I’ve done some big tough MTB rides over the years. La Ruta, Kokopelli’s Trail, OTGG, and others of Stefan’s and my own devising. From a fitness perspective I knew what to expect. It takes several months to a year of serious training to get into the best physical fitness you can. You’re going to be pedaling for 10-12 hours over rugged terrain, miles of tire-sucking sand, and incredibly steep grades (> 25%) that make its 100 miles feel more like a 200 mile road ride.

The best time to ride WRIAD is in spring or fall. This means near the equinox, so you’ll have about 12 hours of daylight.

You need a day-use permit that you can get a day or two in advance, cost about $6. And you need to pay another $15 to enter the national park.

Plan on 11-12 hours total if you stop only once or twice during the ride. That means enough food and water to carry you through. Everyone is different; here’s what worked for me. I had 224 ounces of water: two 100 oz camelback bladders, plus a 24 oz. water bottle. I used all but 12 ounces of it. For food, bring some real food for lunch (sandwich, burrito, etc.) and about 240 cals per hour to eat while you’re riding. Have this food ready to eat while riding because if you stop to eat every hour, you might not finish the ride in daylight.

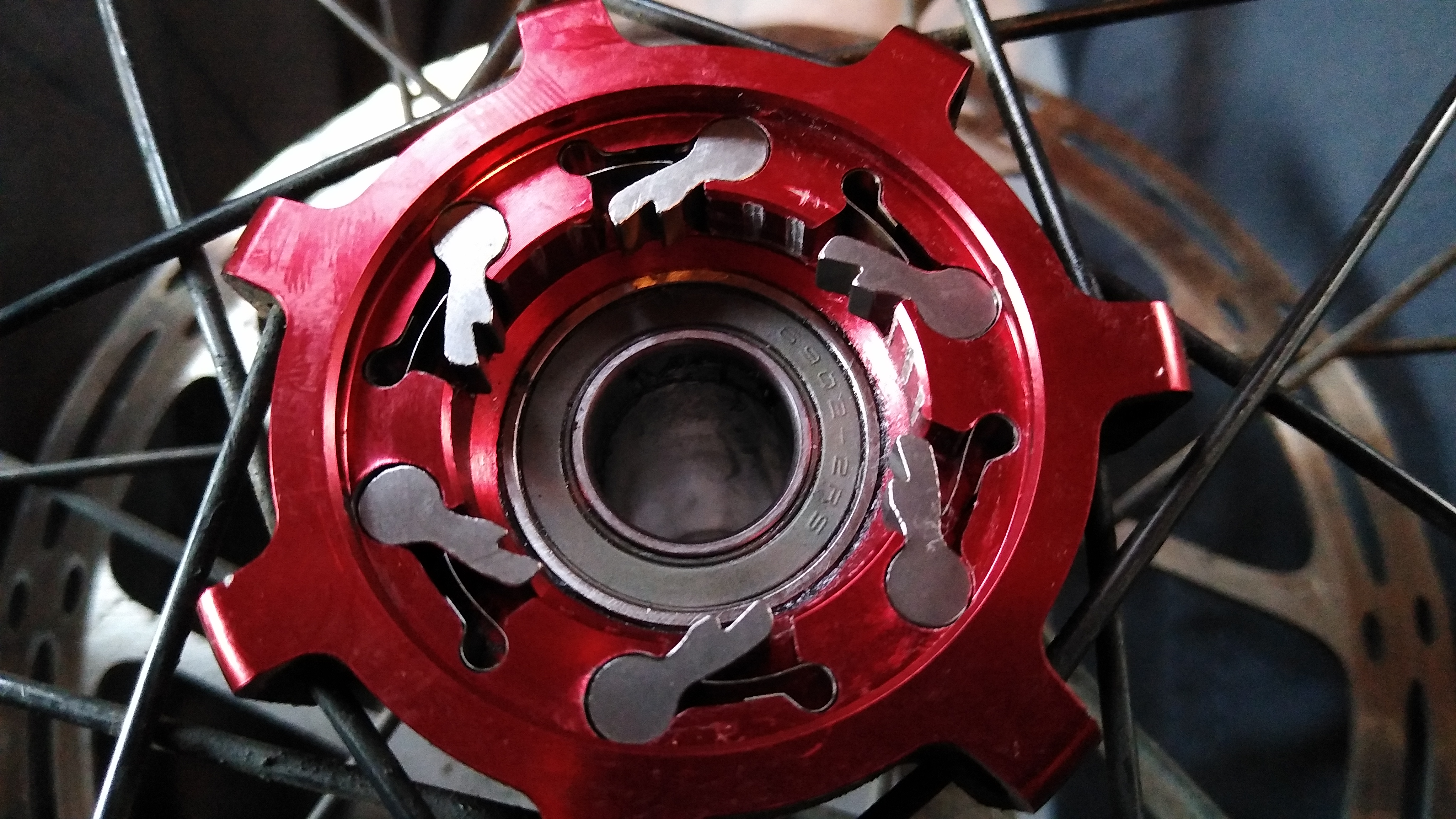

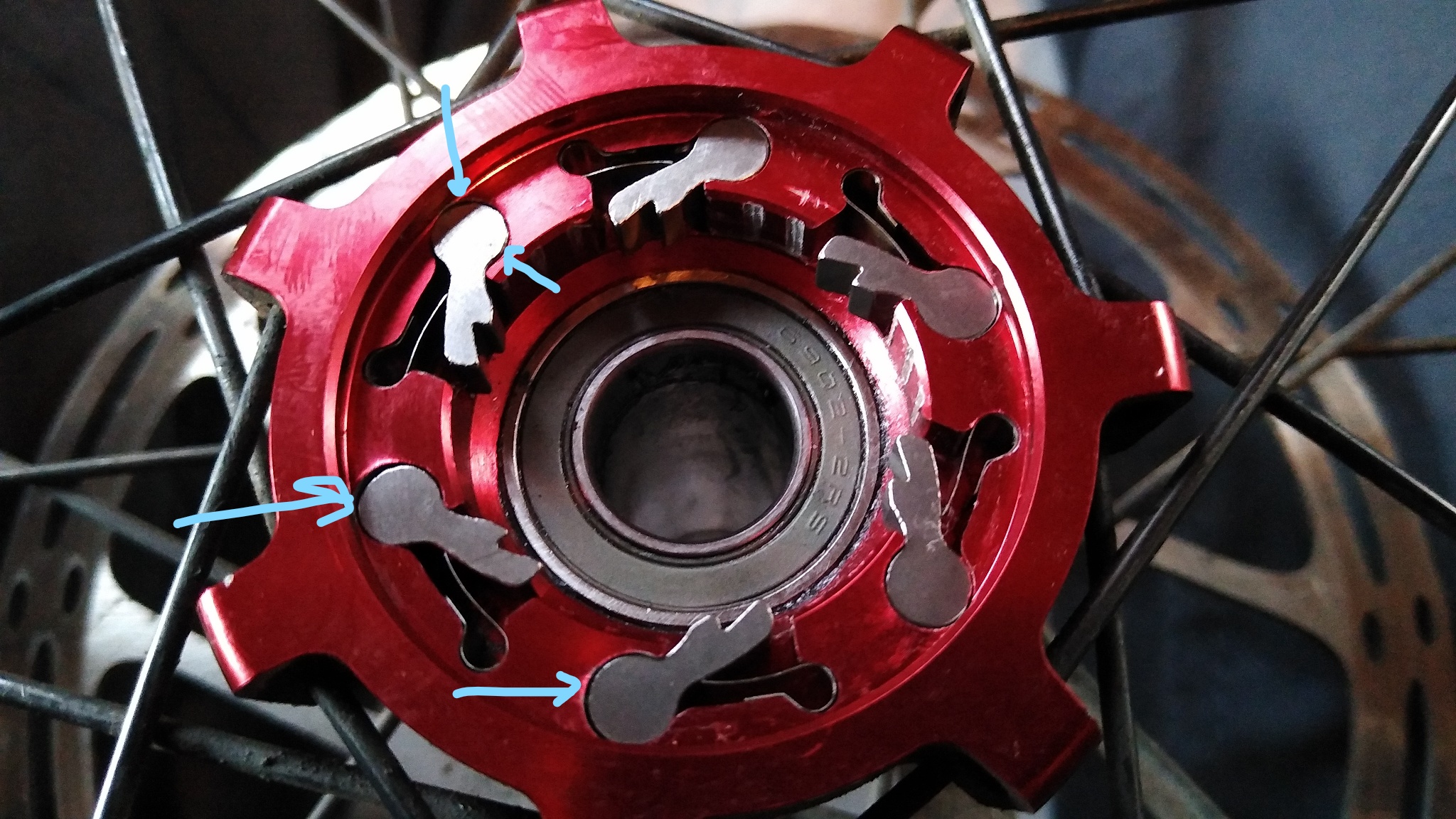

Have a bike that you trust, proven to stand abuse. A bike mechanical failure that strands you along the trail can keep you there overnight and become a life threatening situation. Make sure the entire drivetrain, axles, etc. are new and fresh. Several sections of the trail are too rugged for a gravel bike. You will need a true mountain bike, hard-tail or full suspension, with knobby or semi-knobby tires at least 2″ or 50mm wide. I used Maxxis Ardent Race, 2.2″ / 57mm and they were great. Anything narrower wouldn’t work, anything wider would make a hard ride even harder.

Clockwise or Counterclockwise?

This is a common question. Both ways are doable. Either way you go, you’ll descend into the canyon then climb back out again. These two points are Shafer on the NE side and Mineral Bottom on the NW side.

Here’s the Shafer grade. Red marker is poised at the top.

Here’s the Mineral Bottom grade. Red marker is half-way up, blue marker is our start/end point.

Also, along the trail in the canyon are 2 big notable climbs, each close to 1000′ with some sections too steep to ride. So no matter which way you go, you’ll have 3 very big climbs, in addition to the constant up and down of the trail.

Climb 1, Murphy Hogback, the up side:

Climb 1, Murphy Hogback, the down side:

Climb 2, Hardscrabble Bottom, the up side:

Climb 2, Hardscrabble Bottom, the down side:

We went clockwise starting from the NW corner of the route: the parking lot and toilet just at the top of the Mineral Bottom Climb. This means starting with a 12 mile dirt/gravel road ride that gradually climbs about 1200′, then turning right onto the paved road that runs into the park. Total distance to the Shafer descent where you enter the canyon trail is about 20 miles. Then you ride another 79 miles along the White Rim Trail, and then climb up Mineral Bottom back to where you started. It’s about 1000′ in 1 mile.

The east half of the ride is easier than the west half. It’s just a bit flatter, less sand, less rugged & technical. So the drawback of the clockwise route is that the toughest riding is in the second half of the ride. However, the Mineral Bottom climb, as tough as it is, isn’t quite as rugged or long as the Shafer climb.

Getting There

I flew from Seattle into Moab in my C-172, Stefan drove from Boulder, and we met at the Moab airport KCNY. We stayed at the Moab Apache Inn. It’s not fancy, but it’s a good place with truly excellent service/management.

Sunrise was at 6:45, so that’s when we started. Temps in early Oct were in the mid-high 50s at the start and got into the 70s during the day. This was fortunate!

The Ride

Our start point was at 4800′ MSL. The way we rode, we started along the dirt/gravel road on a long gradual climb. This was nice because it was cool out and the climbing kept us warm so we didn’t need to bring jackets that we would only doff later and carry all day. At mile 12 we reached the paved road (Hwy 313) which is near the peak elevation of about 6000′. We turned S towards the park. After entering the park, a short distance more put us at the top of the Shafer grade with 20 miles on the odometer.

The Shafer descent is just rugged and steep enough to keep you on your toes. If you slide out and miss a turn it could lead to a fatal fall. It was no problem on my full suspension bike but you would not want a gravel bike or skinny tires. It’s incredibly scenic. A short distance and about 1000′ of descent later, you’re in the canyon on the trail. To call it scenic is a grave understatement. It’s stunning.

Here (red marker) is where we had lunch, around mile 55:

For the next 43 miles or so you ride along the rims of canyons, weaving in and around following the contours. Then you reach one of the big steep climbs at Murphy Hogback Canyon. Some parts of this are too steep to ride. It just goes up and up. The top levels off for less than a mile then you go down an equally steep opposite side.

The next 20 miles or so is a gradual downhill, but don’t let the word “downhill” fool you. It’s got long sections of soft sand which sucks down tires, forcing you to pedal hard at slow speed despite the downhill grade.

At this point I encountered nutrition difficulties. I brought Kind bars to eat throughout the day, because they are low sugar and worked great for me in all-day rides over the years. Yet starting around mile 65 I couldn’t keep them down; as I ate them I got a strong urge to barf them back up, so I had to stop eating them. Fortunately, Stefan had some spare Fritos and I had no problem eating those. I never considered chips to be an ultra-endurance food, but sometimes during adversity we learn new things about ourselves. In hindsight it makes sense: Fritos are simple carbs (but no sugar), plenty of salt, and calorie dense. I don’t think the problem was electrolyte loss because I had Nuun mineral tablets in all my water.

Then you reach the second big climb, Hardscrabble Bottom. It’s every bit as tough as the Murphy Hogback climb, ultra steep with some sections too steep to ride. Ride along the top for about 2 miles or so, rolling up and down varying from decent to rough technical conditions. Then back down the other side takes you to around 4000′ MSL about the level of the Green River.

Now ride along a decent quality trail following the Green river for about 15 miles or so, mostly flat. Then around mile 99 you reach the right turn to go up Mineral Bottom. Only 1 mile to go, but it’s very steep, nearly 1000′ climb.

At the end of the ride I didn’t feel right – eating or drinking would have triggered vomiting. I think it was temporary over-exertion because over the 1st post-ride hour I slowly sipped 12 oz of water and kept it down, and over the next hour I felt fine. An hour later we ate a big dinner in town, no problem.

Conclusion

WRIAD was a bucket-list ride for me. The preparation and execution consumed nearly a year of my life. I got into the best physical condition I’ve ever been, similar to doing La Ruta over 20 years ago. Even so, it was one of the toughest rides I’ve ever done, if not the very toughest. I’m pretty sure I’ll never do it again, but big rides like this come with satisfaction and confidence equal to what you put into them. Thanks Stefan for suggesting this one! It was an epic adventure.