When CDs first came out in the 1980s they sounded lifeless. I still have several in my collection from those years and they still sound dull. In some ways they were better than LPs: no background rumble or hiss, much cleaner and tighter bass, uncolored midrange, and consistent sound quality unlike LPs that sound best in the outer groove with sound quality gradually deteriorating as the record plays and the needle moves toward the inner groove. At the end of the record, just when the orchestra is reaching is crescendo finale, you hear audible distortion or dynamic range compression because the inner groove can’t handle the dynamic range. CD avoided these issues. Yet by “lifeless” I mean the midrange detail, high frequencies and transient response on CD sounded worse than LP.

Over the 1990s, CDs improved until around the year 2000 I thought the best CDs had surpassed LPs, with better sounding high frequency and transient response, while retaining the other advantages they had all along. By this point, the best CDs of live acoustic music sounded more natural and real, where the best LPs sounded like an artistically euphonic sonic portrayal.

Looking back, one contributing factor to this transformation of CD audio quality may be the use of poorly implemented anti-aliasing filters in the early days. Over the 1990s, we owe the improvement in CD quality largely to digital oversampling and more transparent anti-aliasing filters, and partially to better implementations of dither and noise shaping.

At the same time, around the turn of the century, high bit rate formats came out: SACD and DVD-Audio. Various engineering and acoustic reasons are given for these high bit rates, most of which are based on well-intended yet fallacious understanding of digital audio, some on blatant pseudo-science.

The best explanation I’ve seen comes from a video by Monty Montgomery, and on his website, where he debunks the most common misunderstandings about digital audio. However, in his zeal to shed the light of math and engineering on this subject, he overstates the case in a few areas. Here I describe those areas. However, while I dispute these points, generally I do agree with Monty. He’s essentially got it right and is worth reading.

Audible Spectrum

Monty says, Thus, 20Hz – 20kHz is a generous range. It thoroughly covers the audible spectrum, an assertion backed by nearly a century of experimental data. This is mostly, yet not quite true. The range of human hearing is closer to 18 Hz to 18 kHz. It’s common for people to hear below 20 Hz, but almost nobody above the age of 15 can hear 20 kHz. For example, at age 50 as I write this, my personal hearing range is from around 16 Hz to 15 kHz.

Ironically, this actually strengthens Monty’s case. Digital audio has no problem going lower than 20 Hz, and we only need to go up to around 18 kHz to be transparent for 99% of people.

The Human Ear: Time vs. Frequency Domain

The ear is a strange device. Highly sensitive, yet inconsistent and unreliable. Our keen perception of transient response is more sensitive than one would expect, given the upper threshold of frequency tones we can hear.

For example, consider castanets. They have lots of high frequency energy, to 20 kHz and above. If you listen to real castanets–not an audio recording, but an actual person snapping them in front of you–the “snap” or “click” has an incredibly crisp, yet light and clean sound. Most recordings of them sound artificial with smeared transients, because these recordings don’t capture those high frequencies well. They’re lost somewhere in the microphone, the position of the mic to the musician, or the audio processing.

I have an excellent CD recording of castanets (it’s a flute quintet, but several tracks feature castanet accompaniment) that has energy up to 20 kHz. It’s one of the best, most realistic castanet recordings I have heard: clean, crisp yet light. Almost perfect sounding. As a test, I’ve applied EQ to this recording to attenuate frequencies above 15 kHz. I can differentiate this from the original in an A/B/X test. In the filtered version, the castanets don’t sound as crisp or clean. It’s hard to describe, but they sound slightly “smeared” for lack of a better word. The effect is subtle, but consistently noticeable when you know what to listen for, and listen carefully.

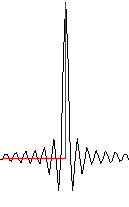

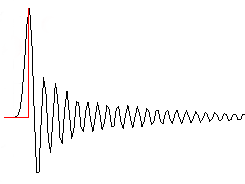

Yet as mentioned above, I can’t hear frequencies above 15 kHz, so I can’t hear the frequencies I attenuated. How is that possible? It may be that the ear is more sensitive to timing than it is to frequency. That is, it can detect transient response requiring higher frequencies to resolve, than it can hear as pure tones. Put differently: take a musical signal of castanets (or anything else with very high frequencies) and apply a Fourier Transform to convert to the frequency domain. The highest frequencies you cannot hear as pure tones. But if you filter them out, it distorts the original waveform in the time domain, rounding off sharp transients and causing pre-echo. The ear can detect these artifacts.

The moral of this story: well-engineered digital audio does perfectly capture any analog signal that has been bandwidth-limited to the Nyquist frequency. But, some caveats apply:

- Bandwidth-limiting the signal can create audible distortion. Anti-alias filtering with a steep slope creates audible time domain distortion in the pass-band.

- Higher sampling rates (alternately, oversampling) give a wider transition band, making a gradual filter slope, reducing this pass-band distortion.

- The frequencies needed for transient response to sound transparent, may be higher than the frequencies that people can hear as pure tones.

Of course, these points are not unique to digital audio. To get transparent transient response, every step in the recording chain must preserve high frequencies. You must use microphones with extended high frequency response, position them close enough to the musicians to capture the frequencies, etc.

Anti-Alias Filtering

The CD standard of 44.1 kHz sampling is not high enough to implement proper anti-aliasing filters that run on normal hardware (DAC chips) in real time. The proof of this assertion is in the specifications of nearly all common DAC chips: at the 44.1 kHz sample rate, their digital filter stop band is 24.1 kHz, which is above Nyquist.

The reason has to do with how aliasing works. Every frequency in the passband has an alias above Nyquist, and these frequencies are always mirrored around Nyquist. For example, at 44.1 kHz sampling the alias of 17 kHz is (22,050 – 17000) + 22,500 = 27,100 Hz. If we stretch the stop band from 22,050 to 24,100, then we allow frequencies from 22,050 to 24,100 to leak through. These are above Nyquist, so they are always noise. But since Nyquist (22,050) is exactly halfway between 20,000 (top of passband) and 24,100 (filter stop band), the passband aliases of this supersonic noise must necessarily all be above 20,000, thus inaudible to humans.

This engineering trick or kludge is clever, but the engineers designing these DAC chips would not resort to it unless it were necessary. At 44.1 kHz sampling, the transition band (20,000 to 22,050) is so narrow it’s impossible to implement a proper digital filter, so they bend the rules. Further proof is that the digital filters at higher sampling rates (88.2, 96, etc.) are properly implemented, with stop bands at Nyquist or lower.

Lossy Compression

Monty says: a properly encoded Ogg file (or MP3, or AAC file) will be indistinguishable from the original at a moderate bitrate. This is downright false — yet it depends on one’s definition of “moderate”. Trained listeners of high quality recordings on high quality equipment can reliably differentiate lossy compressed audio even at high bit rates (like 320 kbps MP3).

A/B/X testing the highest quality recordings in my collection, I can reliably distinguish MP3 up to about 200 kbps rates, using LAME 3.99.5, which is one of the best encoders. With some specialize recordings (jangling keys, castanets) I can differentiate them at the max 320 kbps rate. Most MP3s are done at 128 to 160 kbps thus could be differentiated from the original.

However, there is some truth to the “moderate bitrates are sufficient” viewpoint. Most MP3s are of rock, pop or electronic music, inferior quality master recordings that are compressed, clipped, and heavily EQed. The low 128 to 160 kbps rates may be transparent for this content. But that’s not relevant to us; here we’re talking about high end.

In short, if you are an experienced critical listener of high quality recordings on high quality equipment, you can hear the difference of MP3 and other lossy compression.

I’ve also got a few thoughts on dynamic range and 16 vs 24-bit. That’s a whole ‘nuther discussion.

Conclusion

What Monty says about digital audio is true, generally speaking. He’s done a great job of debunking common myths. High bit rate recordings are over-hyped and can actually be counterproductive. However, there are some caveats to keep in mind:

- High bit rate recordings often do sound better, because when they are being made, extra care and attention is used throughout the entire recording process.

- But if you took that recording and down-sampled it to CD quality using properly implemented methods, it is likely to be indistinguishable from the original.

- High bit rate recordings may be sold as “studio masters”, not having dynamic range compression, equalization or other processing often applied to CDs.

- This is related to (1), and the same comment applies.

- High bit rates can offer subtle improvements to transient (impulse) response.

- This benefit is intrinsic to high bit rate audio

- However, it is not always realized because the limiting factor for transient response may be the microphones or other parts of the recording process.

- High bit rates can sound worse, because they may capture ultrasonic frequencies that increase intermodulation distortion.

- The differences that high bit rates make (improvement or detriment) are subtle and most people don’t have good enough equipment or recordings to hear the differences.

Parting Words

Engineers may want to record at higher sampling rates with more bit depth to give headroom for setting levels and other processing. But their final result can virtually always be transformed to 44-16 without any audible compromises (distortion, compression, or loss of information). Yet in some areas, 44-16 while sufficient, is barely sufficient, which means it requires careful well engineered over-sampling, anti-aliasing filters, noise-shaped dither, etc.

High bit rate recordings, when done carefully, can offer slightly better transient response for certain types of music. But to the extent they actually do achieve this by accurately capturing higher frequencies that improve transient response (which is rare), this HF content is a double-edged sword that brings the risk of higher IMD distortion. Of course, high quality well-engineered audio gear (DAC, amp, speakers, etc.) mitigates this risk.

If you do use high bit rates, it doesn’t take much more than 44,100 to get the benefits. You don’t need 192k or higher. Most likely, 64k sampling would be enough to get all the advantages. But since that rate is never actually used, we’d go to 88,200 (twice the normal CD rate).

Some practical guidelines:

- If the original recording was made in the 1980s or earlier, there is no point to high bit rates. Ultra high frequencies are already non-existent or rolled off, transient response is already imperfect, dynamic range is already limited. Here, the 44-16 standard is higher fidelity than the original.

- If it’s rock, pop or electronic (whether old or new) there’s probably no point to high bit rates. It’s already heavily processed and there is no absolute reference for what this kind of music is supposed to sound like. Classic rock/pop albums get re-released every few years with different re-masterings that all sound different. One version may have better bass or smoother mids, but that is not a 44-16 limitation. Which release is “best” is not a limitation of digital bit rate, but only a matter of opinion.

- If it is acoustic music recorded in natural spaces, a high bit rate recording may be useful, especially if the recording has very high frequencies (castanets, bagpipes, trumpets) or transient impulses. Even if the bit rate alone doesn’t help things, the entire recording is probably (though not always) made with more careful attention to detail and high engineering standards.

Overall, I don’t worry about it. The quality of a music recording depends far more on the mics used, their placement, the room it was recorded in, mixing and mastering, than it does on the bit rate. And 44-16 is either completely transparent, or so close to transparent that even on the highest quality equipment with the most discerning listener, limitations in other areas of the recording process make the differences mostly moot. However, for these rare special excellent recordings, I will get high bit rate versions if they’re available, if they haven’t been remastered and reprocessed to squeeze the life out of the music, and they don’t cost more than the CD.